The Illustrious Field Term

As the class of 1964 crossed the Commencement stage, Beloit College was poised to start a revolution in higher education. The class of 1968, the college’s next cohort of new students, would soon arrive and make history as the first class recruited on the prospect of the new “Beloit Plan.”

The Field Term was a defining feature of this bold year-round curriculum aimed at experiential learning. Originally directed by Hugh Allen and later John Biester’41, the Field Term demanded a unique schedule to accommodate and facilitate off-campus experiences.

“Beloit College was a pioneer in the special concept of a single required off-campus term with a calendar that permitted students to extend the experience up to a full year or to arrange alternating work and study periods over a 20-month span,” Biester wrote in the introduction to an unpublished book on the history of the Field Term.

By the late 1970s, under College President Martha Peterson’s administration, the college began moving away from the Beloit Plan, and Beloit returned to a two-semester schedule. Although a handful of Field Terms continued into the early 1980s, the decision was made to remove them as a requirement in 1978. As the Field Term became optional, a dwindling number of students opted to take part.

While the Field Term may have officially ended in the late ’70s, it never really went away. Its spirit has lived on through requirements and expectations of Beloit students over the spanning years, including in the college’s noted study abroad program and most prominently in the contemporary curriculum. Put in place five years ago, the current curriculum echoes the Beloit Plan by re-emphasizing the importance of experiential learning. Two years ago, the college also launched a summer program called the Field Experience Grant, a chance for students who qualify to apply for a self-designed, off-campus project they complete the summer after their first year.

Students create a proposal with a defined budget and then go through an approval process, explains Cristina Parente, Beloit’s Field Experience coordinator. Much like the Field Term, students file a Field Experience Grant reflection paper at the end of the summer. Last year, 47 first-year students took advantage of the opportunity, and this summer, 87 students are planning to take part. Projects so far have included flying lessons, Java software coding camp, research in the Boundary Waters of northern Minnesota, and herding goats. Similar to the Field Term, Parente says, “There are no rules—other than that it be safe, feasible, and possess some learning outcomes.” She hopes that in the coming years every entering Beloit student will be eligible to pursue a Field Experience Grant.

Meanwhile, the influence of the Beloit Plan Field Term lives on in the legacies and memories of the alumni who, in the late 1960s and 1970s, found themselves scattered across the world—on globe-trotting motorcycle trips, at NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center in the run-up to the moon landing, as deckhands on yachts docked in the Caribbean, registering black sharecroppers and 18-year-olds to vote, and crossing Times Square at all hours while working as “copyboys” and “copygirls” at the New York Times.

The sheer variety of these experiences represents the broad aspirations of Beloiters. Marjorie Hanft-Martone’76, who spent her Field Term working at an EMI Records store in London, said the term opened her mind to a global world. Lori Lippitz Chinitz’79, who went on what would be one of the last Beloit Field Terms, taught versions of John Denver’s song “Country Roads” and other music to the children of diplomats living at the American embassy in the Soviet Union.

The more than 5,000 Field Term placements were so wide-ranging and life-altering, it would be impossible to account for them all without publishing a book. The following pages offer a glimpse at what the Field Term meant to a handful of alumni who were part of a unique moment in the history of Beloit College and American higher education.

San Francisco and Guam

Last year, Caroline Burkat Hall’76 and her husband, Henry Hall’77, took a trip to visit their son in San Francisco. It was Caroline’s first time in San Francisco since her Field Term back in the summer of 1974. Walking around the Bay Area not only brought back memories of the summer Richard Nixon resigned, but it also made her wonder: What did other people do on their Field Terms?

She posted that question to the Unofficial Beloit Alumni Digest on Facebook and hundreds of Beloiters from the Beloit Plan era responded with memories of their Field Terms.

For her part, Caroline was a history major who wanted to be in San Francisco from the beginning. “I just thought it would be interesting to work there,” she says. Her position at the Presidio School gave her an opportunity to be in a classroom a few weeks before the school converted to a summertime day camp.

At the time, the Presidio School was where many prominent San Franciscans, including Warren Hinckle of Ramparts magazine, sent their children. “It was not your typical private school,” she says. “It was an artsy school.”

Caroline says she enjoyed having her first taste of self-sufficiency. Out west, the New Yorker, used to taking trash to her building’s incinerator, encountered recycling for the first time. She spent her weekends heading to Union Square or Powell Street and visited the recently opened national park on Alcatraz Island. She bought a fake ID, “my one and only,” to attend a 21-and-over Jerry Garcia concert at the Great American Music Hall.

She also managed to maintain her relationship with her boyfriend and future husband, Henry Hall, who was spending his Field Term, followed by a vacation term, on the island of Guam. They first met during New Student Days and started dating in September 1972.

“Phone calls had to be scheduled in advance,” she says, “and it cost about $25 to make a three-minute phone call.” At the end of her Field Term, she flew to Guam and stayed a few weeks before returning to the mainland for the rest of her vacation term.

Asked what he had done on his Field Term, Henry Hall replies, “I raised hell.” He worked as a substitute teacher, a swim coach, and a proofreader at a newspaper during his time on the island. He also played trombone in a rock band called “Bamboo,” which opened for Chuck Berry in August of 1974.

“The band kept us pretty busy,” Henry says. “We played six nights on, then six nights off. For the most part we had one steady gig at a bar—it was a bit of a dive to say the least,” he laughs.

Guam, besides being a “subtropical paradise,” was also an interesting locale given that the Vietnam War was winding down. “The island had a population of about 120,000 at the time, and half were military members,” Henry says. B-52s on their way to Vietnam were taking off every seven minutes around the clock during the summer and fall of 1974.

While Caroline says her Field Term gave her a sense of greater maturity, Henry jokes that his was a different experience. “I saw the world, beautiful oceans, and I spent a lot of time on the beach,” he says. But both had that chance to live in a different part of the world and to enjoy an experience far removed from the classroom. The Halls’ experiences were, to say the least, the sort of opportunity that could only happen on a Beloit Field Term.

The ’68 Presidential Election

Amid the upheaval of 1968, a pair of Beloiters, Catherine “Catey” Doyle’69 and Vicky Herring’70, were at the center of one of the most bizarre and memorable presidential campaigns in modern American history. Doyle spent her Field Term working at Eugene McCarthy’s presidential campaign’s national headquarters in Washington, D.C., and wound up organizing in Milwaukee and Beloit during the Wisconsin primary. Herring, on the other hand, worked for the Democratic Party laying the groundwork for the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Before their Field Terms were over, both would see National Guard troops marching down the thoroughfares of two of America’s great cities.

As New Hampshire approached, the campaign office began to change. “My days became very busy. The phone rang every few seconds, the typing piled up,” Doyle wrote in her Field Term report. “I became the general information dispenser and took most of the phone calls regarding volunteer work, setting up of new headquarters, and the Senator’s schedule.”

The New Hampshire primary was the game changer. President Johnson won 49 percent of the vote in the primary, and McCarthy received 42 percent. “Two days after the New Hampshire primary, I was told that I was to go to Wisconsin for the primary on April 2,” Doyle reported.

The Wisconsin primary became all-consuming. After a week in Milwaukee, Doyle was dispatched to set up an office in Beloit. “The two weeks in Beloit were the most fun and rewarding of my entire life,” she wrote. McCarthy spoke on campus, and Doyle set up shop in an eight-room storefront on State Street.

She even shaved a few mustaches and beards for campaign volunteers because “the slogan ‘Clean for Gene’ was a reality,” she wrote.

On primary day, McCarthy took home 68 percent of the votes cast in Beloit and went on to win the Wisconsin primary. Two days earlier, Johnson had sent shockwaves through the electorate when he announced he would not seek re-election. The McCarthy primary victory celebration didn’t last. Two days later, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis.

Doyle flew back to a Washington, D.C., coming apart at the seams. Her plane landed soon after the first curfew was imposed. Her roommates had left messages with the airline for Doyle to meet them at a different apartment because their place was surrounded by rioting. She stayed with six other people in an apartment for two days before eventually returning home.

While the McCarthy office remained closed until after King’s funeral, Doyle turned her attention to the scene outside. “The evenings of that week were spent watching the troops roll by our building. The city was like a foreign country,” she wrote. “Two soldiers stood guard outside our building every night.”

In early August, following Robert Kennedy’s late-entry to the race and his assassination, and the party leadership’s intention to support Vice President Hubert Humphrey for the nomination, Doyle wrote that, “For many of us, the campaign brought the first real ray of hope in several years. As of today, however, we are all afraid that the hope we found may be dying in a system too old and traditional to change even when the majority of people favor that change.”

• • •

Originally from Des Moines, Iowa, Vicky Herring’70 had moved with her family to the Washington, D.C., area when her father went to work for the federal government. Although she had already worked one term at the Department of Education, a family friend who was secretary of the Democratic National Committee, suggested she do an internship helping to lay the groundwork for the convention in Chicago.

During the run-up, she handled a fair amount of “grunt and arrangement work.” There were some perks—she took Mahalia Jackson to lunch and ran into a shirtless Paul Newman.

As the convention got underway, the infamous anti-war demonstrations and heavy-handed police response were in full view of reporters and camera crews. As the acrid smell of tear gas plumed over Michigan Avenue and Grant Park, Herring recalled a putrid smell taking over the interior of the Hilton Hotel, which was in the midst of the turmoil. “The demonstrators put a repulsive cheese inside the cooling and ventilation shafts,” she says.

As the eyes of the nation were on protestors chanting “the whole world is watching,” Herring’s eyes were on the man accepting the party’s nomination: Humphrey. “Finally, when the vice president [Humphrey] was going to go to the platform to receive the acclaim of the convention, I got a floor pass (as did almost everyone else) and I went to the floor,” Herring wrote in her Field Term report. “When the time came, the emotions pent up in me since early July came loose, and I joined in the joyous demonstrations—and I am proud to say that even in light of the disturbances, I think we nominated the best man for the office (though I believe that the best man was shot in June.)”

Being at the center of that great conflagration didn’t temper Herring’s taste for politics. She worked for Congressman Les Aspin, later Secretary of Defense under Bill Clinton, and practiced law in the civil rights division of the Iowa Attorney General’s office before moving into private practice in the early 1980s. Today she runs an art gallery called Artisan Gallery 281 in the Valley Junction neighborhood of West Des Moines.

The upheaval at the convention did not taint her feelings about the Field Term either. “In a sense, the Field Term broadened my horizons. If you stay in college all the time, you have a lot of intellectual discussions. Lord knows you’re solving the world’s problems at 3 a.m., but the reality of life is that you can’t solve all the world’s problems at 3 a.m.”

Beloit Tutoring Center, Cleveland, Miss.

Michael Young’69 can divide his life into a time before his Field Term at the Beloit Tutoring Center in Cleveland, Miss., and his “vacation term” working with the Delta Ministry registering voters—and his life after he returned to the north.

“My Field Term was the most important experience of my life,” Young says. “I saw so much that was wrong, so much that was unfair, so much that was evil and hate-filled. My Field Term clarified for me what side I was on, what values I would pick, and the lens through which I would see the world.”

Young says that “Everything was clear in Mississippi in a sense that there is black and white. White neighborhoods looked like any suburban neighborhood in the country—they had lawns, streets, curbs, and sidewalks. Black neighborhoods had no pavement, only dirt roads, very few lawns.”

While legal segregation was over in places like movie theaters, de facto segregation had become the law of the land. Young recalls going to a movie theater in Clarksdale, Miss., where the balcony remained a section only for black patrons while the main floor was only for whites. He found the same thing at bus stations.

Working with the tutoring center, a college outreach program, along with a pair of other Beloiters, Young had a number of responsibilities. One part of his job was tutoring—children and some adults, mostly tenant farmers and sharecroppers, in basic literacy and basic mathematics. Young also took on the responsibility of getting nine black students to the newly integrated white school each day.

“Forced integration had just taken place. The students were allowed to attend the school, but the school district wouldn’t bus the group to school,” Young says. “So I drove an old International Harvester truck, a big old mail truck. Every morning, I’d pick up the students and drop them off at school, and then every afternoon I’d pick them up and drop them off back home.”

The daily round-trips weren’t without risk.

“There were always rumors, and things happened in other parts of Mississippi. Once I remember driving the truck with some kids in it and guys in cars started buzzing us. There was always that lingering notion,” Young says, “that there was some risk there. But I think we benefited from being young people, being relatively invincible, and caught up in believing that what we were doing was the right thing to do. That was the saving grace.”

Spending his “vacation term” working as a field organizer for the Delta Ministry seemed a natural outgrowth of the work he had been doing for the BTCM. Young had gotten to know Owen Brooks, the head of the Delta Ministry and his field staff. One of Young’s responsibilities with the Delta Ministry was voter registration.

“Among the components of the job was to go meet black residents on plantations, really, in the heart of cotton country, and convince them to vote. Then we’d have to get them to the county seat where they could register. Everything was structured to undermine the capacity of blacks to vote,” Young says.

When Young returned to campus, he took a more active role in the Afro-American Union, and eventually served as AAU’s president when it delivered the “Black Demands” at the historic 1969 Middle College sit-in. Some of the demands, Young notes, are similar to those that students of color are still calling for at academic institutions across the country.

In addition to Black Demands, Young took his experiences in 1960s Mississippi in other important directions. “I came back a different person, and I challenged Beloit using what I’d learned on the Field Term,” Young says. “It allowed me to see things, I’m not sure I saw clearly, until my Field Term.”

At the time, Beloit had been trying to reach out to local minority youth, and Young got involved in those initiatives when he returned to campus. Among the programs designed to bring low-income Beloit high school students and students of color to Beloit’s campus was one was called the High Potential Education Program.

After graduating with a master’s degree from the University of Michigan, Young returned to Beloit, and eventually became the director of the HPEP. He also oversaw an effort to provide more student services in support of black students on Beloit’s campus. After attending a conference on programs similar to HPEP nationwide, he met another mentor, who much like his professors and mentors at Beloit, helped him realize he could have an even larger impact with a Ph.D. in higher education administration. After graduating from the University of Iowa, Young headed west and eventually became the Vice-Chancellor for Student Affairs at the University of California-Santa Barbara.

Young says the Field Term set it all in motion. “It led to those choices: to come back to Beloit, to work in the High Potential Education Program, and to bring significant numbers of black students from the local community into the fold at Beloit College,” he says. “My experience on the Field Term drove my professional goals, my interest in that kind of work, and it remains so to this day. The Field Term clarified how I would live my life.”

From East Coast to West Coast

Richard Rounds’72 had a one-of-a-kind Field Term photographing his peers’ Field Terms.

By the fall of 1967, Richard Rounds’72 had a bit of a reputation on campus as a photographer, given his work on the college’s yearbook. Around the same time, the Field Term office was in need of a way to document and represent the program to parents, admitted students, and alumni.

“The Field Term idea really came out of the blue,” Rounds says. “Somebody in the Field Term office approached me.” How would he feel about spending his term traveling across the country photographing other Beloiters’ Field Terms?

In the winter of 1968, Rounds left his parents’ home in Rhode Island armed with “less than a shoestring budget.” The Field Term office had provided him with $300.

For the most part, he worked east to west, traveling thousands of miles and spending an inordinate amount of time flying standby at the student rate, taking cross-country bus trips, and bumming rides.

The Field Term office sent a letter to students that Rounds would be visiting. “If you can help him out, please do,” the note said. Rounds says he’d arrive in town, give a student a call, mention the letter, and ask to crash on his or her couch. “Back in those days, that was normal business. It worked great,” he says.

His first stop was the American Shakespeare Theatre in Connecticut. Soon after came days in Boston photographing students at employers such as Liberty Mutual and IBM. “I’ll be the first to admit I really didn’t know what I was doing,” he says. Rounds claims he became a much better photographer after the college hired Michael Simon to teach photography.

“The theory behind my Field Term was to make the Field Term look appealing,” says Rounds. “I knew I wasn’t going to get anywhere with photographing people sitting in an office, so I’d look at the locale.”

Rounds’ enduring memories of his two weeks in New York include learning how to navigate the city’s subway system and venturing inside the Statue of Liberty’s torch, which has been closed to tourists since 1916.

In the nation’s capital, he made his way inside Ford’s Theatre and found himself on an official congressional tour of the White House, thanks to a Beloiter working in a congressional office.

His trip out West left plenty of indelible memories. “When I was in San Francisco, a number of Beloiters were working for elementary school groups, which brought students out into the wilderness for a week,” he says. “The redwoods were incredible. One of the sites was close to an area where logging was going on. You could climb to the top of this downed redwood and walk on a tree that was almost the length of a football field,” he says.

In Taos, New Mexico, he saw mountains for the first time, and in Santa Fe, he spent his only night in a hotel for the length of his Field Term. “It was $3 for a room without a bath and $3.50 for a room with a bath,” he says, “so I splurged.”

Rounds did most of his work developing the 35 millimeter black-and-white film back at Beloit in a makeshift darkroom located in the arts center lecture hall.

After graduation, Rounds got a start in commercial diving in Wisconsin. In 1980, he journeyed to St. Croix in the Virgin Islands, where he worked for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hydrolab Project, an undersea habitat he went on to direct. He also worked on Aquarius, another major underwater lab studying marine ecosystems in the Virgin Islands. Both labs were among the most successful and long-lived undersea research habitats in the world. Though Rounds was mainly involved with ocean engineering, he put his photography skills to use in his work both above and below water.

When he retired in 2013, Rounds returned to Rhode Island.

Although he lost touch with some of his friends from Beloit, he has kept up with his photography.

He clearly recalls a definitive theme among the Beloiters he photographed across the country. “If I felt anything traveling around, it was a lot of enthusiasm for the Field Term,” he says. There was also a universal connection to Beloit. “Maybe I’d seen them on campus or they’d seen me, and though we really didn’t know each other well, we got to be friends quickly,” he says of fellow students. “Even though we were spread out across the country, we were a big family.”

Joe Engleman is a Chicago-based writer who also works in media relations for the Chicago Humanities Festival.

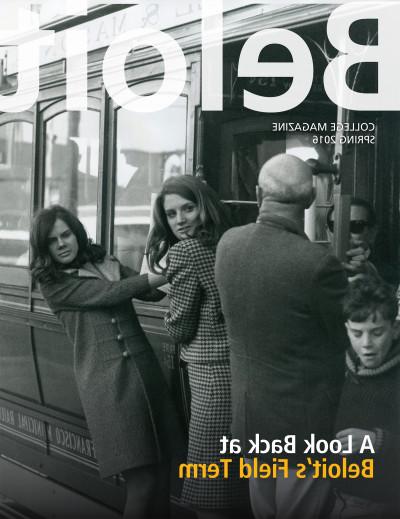

About Field Term photography

In 1968, with a budget of $300, Richard Rounds’72 documented the Field Term for Beloit, making as many as 50 photographs that offer a window into the past. The collection was originally used in the late 1960s to recruit prospective students to Beloit. It is now among the holdings in College Archives.